pdf version: BoC balance sheet COVID

Introduction:

It seems fitting that in the anniversary of its 85th year the Bank of Canada has come full circle and is back to its roots using the same kind of monetary tricks it employed in 1935 to start pulling Canada out of the Great Depression (plus a few new tricks). Neoliberal governments the last 40 years have hoped Canadians forget the progressive past of our publicly-owned central bank aiding the people, but it’s come back to the forefront in a way now that will be hard to ignore.

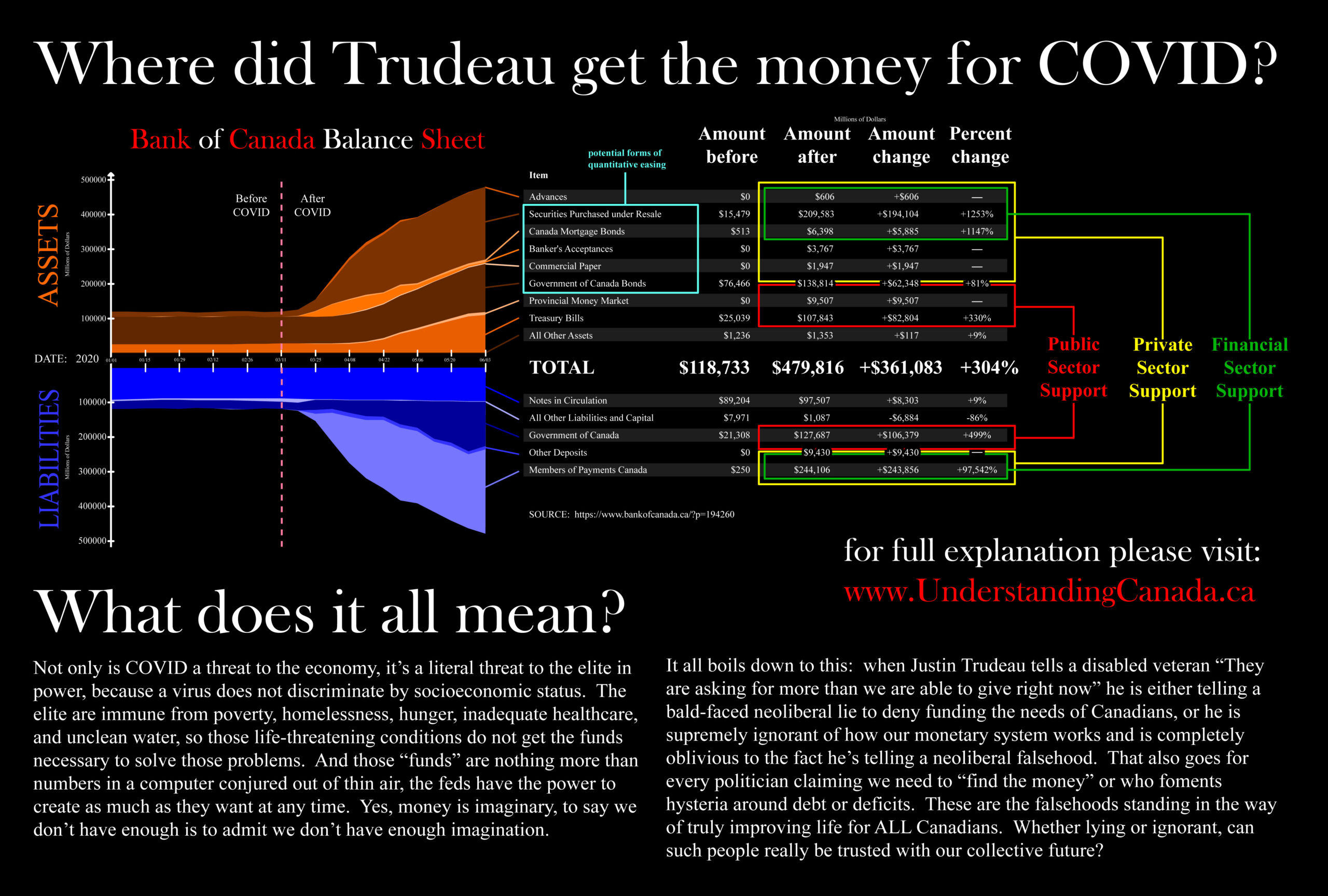

The $361 billion (and counting) question? WHERE DID THE FEDS GET THE MONEY FOR COVID SUPPORT?!? Well, the answer is as simple as it always has been: where does all money come from? OUT OF THIN AIR!!!

Yes, for those of you reading this information for the first time, it’s true, we live in a debt-based fiat monetary system, pretty much all money is created as debt, and there is nothing backing our money (like gold or silver) other than confidence in our economy. Here is a federal government page admitting to that fact: “Both private commercial banks and the Bank of Canada create money by extending loans to the Government of Canada and, in the case of private commercial banks, lending to the general public.”

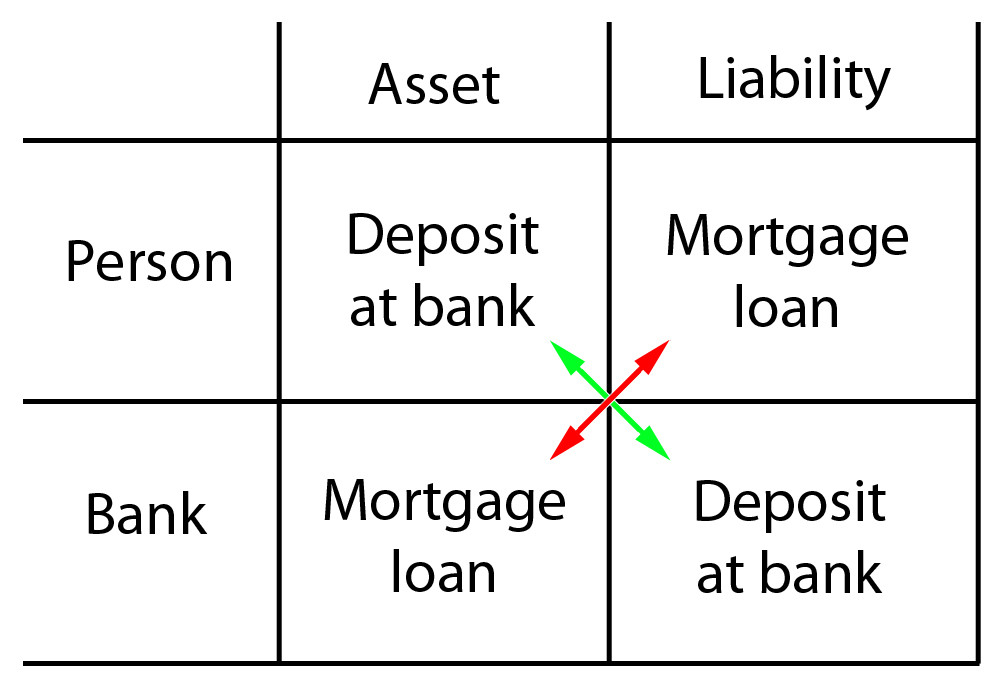

When your bank gives you a loan, or line of credit, or mortgage, they don’t lend you their own money, they don’t lend you their depositors’ money, they type numbers in a computer and POOF! New deposit money you can spend, matched by the new debt you rack up, it’s all just numbers on a digital ledger. The flip side is that repaying a loan destroys that new money, and all that is leftover is the interest you pay to the bank. If we paid off the principal on ALL the debt there would be no money left, only the unpaid interest. And so new debts pay off old debts in a never ending spiral of growing debt that grows the almighty GDP.

Well it’s that simple for the government too, our public central bank has the ability to create ANY money the government should require to finance the solution to any problem. Here’s another great quote from the feds themselves about how the federal government can never go broke and will never have difficulty finding funding: “As the nation’s central bank, the Bank [of Canada] is the ultimate source of liquid funds to the Canadian financial system and has the power and operational ability to create Canadian-dollar liquidity [money] in unlimited amounts at any time.” In unlimited amounts at any time.

So, why don’t they create more to solve Canadians’ problems? Well, neoliberal governments serve the profit needs of the private sector first, they don’t actually want to solve society’s problems, they merely want to create the illusion they are helping, just enough to get re-elected. Which is why they never give quite enough money to actually solve anything unless it’s to bailout a favoured supranational corporation.

But in a crisis with such macroeconomic ripples as this, to give the economy the support it needs the government and central bank have no choice but to tip their hand and reveal just how easy it is to turn on the money taps when the wealth vacuum for the elite we call an economy stops functioning. Not only is COVID a threat to the economy, it’s a literal threat to the elite in power, because a virus does not discriminate by socioeconomic status. The elite are immune from poverty, homelessness, hunger, inadequate healthcare, and unclean water, so those life-threatening conditions do not get the funds necessary to solve those problems.

As it turns out, maintaining those problems serves to strengthen the neoliberal system by creating conditions of stress, scarcity, and desperation that suppresses wages and keeps people seeing each other as the competition instead of cooperating. If people are too busy struggling to make ends meet they don’t have time to think about what their politicians are doing, never mind taking action. It’s one of the primary ways elite neoliberals keep as many people as politically disengaged as possible to ensure there is no “excess of democracy“.

The long and the short of it is this: our federal government does not have to “find the money”, it has ALWAYS had the power to create whatever it needs if it so chooses. The only reason they don’t is purely ideological and caters to the needs of the wealthy, our largest corporations, and the financial sector. While there are real world constraints to increasing government spending on the public, we’ve never truly seen what they are because our governments serve the profit needs of the private sector first, and everything else second. We’ve never known how many more problems we could solve if our products, services, and resources were dedicated to improving the public good first (like ensuring ALL Canadians have reliable access to clean water and healthcare or a roof over their heads), instead of being monopolized to ensure corporate profits and being squandered on things like luxury cruise liners and military equipment.

It’s simply the nature of a capitalist economy in a debt-based monetary system: if most of the economy is privately-owned and all money is debt, then if the government doesn’t maintain those private profits the debts can’t be repaid and the whole house of cards comes crashing down. Under this inequitable unsustainable system politicians really have little choice but to support the prioritization of the profits of our largest corporations because if there’s a corporate profitability crisis and companies start defaulting on their debt the economy will collapse. Either that or our “leaders” could, you know, advocate for a system NOT based on making a tiny minority of people exceedingly wealthy thereby empowering those ultra-wealthy to monopolize our resources and direct public policy to their own greedy ends?

But you’re not here to listen to a diatribe about the neoliberal inequality engine we use as the system to run our lives (or maybe you are?), you’re here to learn how the government can create all the money it needs for social good through our central bank. It’s really quite simple….

How it all works:

The Bank of Canada creates money primarily two ways: it can create it to loan to a bank or government (an “advance”), or it can create it to buy financial assets like bonds, treasury bills, and many other kinds of securities. Advances rarely happen, especially advances to governments (here’s a short list), but the latter method happens all the time, if not daily.

I won’t go too deeply into details about the mechanics of all this, because in the aggregate the daily moves of the BoC are quite an intricate dance ensuring stable predictable flows in the financial system. Just look at how even the balance sheet numbers were before the crisis, the BoC works very hard to keep those numbers steady, shuffling assets and liabilities around multiple times a day to get its balance sheet, and consequently interest rates, right where it wants them.

While the government has many different accounts for itself and its various Crown corporations, all the funds for COVID are coming out of the Consolidated Revenue Fund, aka the Receiver General account, at the Bank of Canada. This is where pretty much all discretionary spending by the federal government originates. BILL C-13: An Act respecting certain measures in response to COVID-19 states “there may be paid out of the Consolidated Revenue Fund, on the requisition of a federal minister and with the concurrence of the Minister of Finance and the Minister of Health, all money required to do anything in relation to that public health event of national concern.”

There is one huge caveat to my analysis of the BoC’s balance sheet: one cannot say for sure precisely what is going on because the BoC is incredibly tight-lipped about all of its inner workings, the motivation for the moves it’s making must be deduced from understanding what each of the items on the balance sheet are and why they would change. Central banks are pretty much a black box, one can track the changes on their balance sheet but they’ll never explain precisely why they took a particular course of action each day. Most of the reason is it makes it impossible to criticize them from the outside, whether you are a sitting politician or a business analyst, but it’s also to maintain the mystery of it all and ensure the public have little chance of ever understanding it. Well this is another of my attempts to pull the wool off our eyes and reveal to the public, as plainly as I can, the reality of banking and the monetary system. Welcome to the rabbit hole…

The Balance Sheet:

The opening diagram is of the weekly averages of the balance sheet of the BoC. Every economic entity, including people, are each their own balance sheet of assets and liabilities. Assets are what you own, liabilities are what you owe. Your house is an asset, your mortgage is a liability. To a bank, your deposits are their liability (they owe it to you), but your debt is the bank’s asset (because you owe it to them).

So what you are looking at on the opening diagram is the total of all BoC assets on the top, and the total of all BoC liabilities on the bottom, both measured in millions of dollars. By accounting convention total assets and total liabilities will always balance, which is why they are a mirror image of each other. As you will note, they both soar after COVID lockdown begins, indicating the hundreds of billions of new dollars the BoC created for the crisis.

But don’t expect the BoC to outright admit that’s what it’s doing; they use bankspeak to obscure the reality. Instead of stating clearly they created hundreds of billions of dollars out of thin air, the BoC states “These interventions, which involve acquiring financial assets and lending to financial institutions, increase the size of the Bank’s balance sheet.” A “balance sheet expansion” is simply money creation, they just refuse to call a spade a spade because that would alert the public to the subterfuge. Fortunately I have been studying the BoC long enough to cut through their Orwellian bankspeak so rest assured I will explain everything as best I can.

I’m learning over time how incredibly hard this topic is to convey to regular folk unfamiliar with even the basics. Many an ignorant person will claim, “if you can’t explain it simply it means you don’t understand it”, but that’s truly not the case, not for particle physics, not for the monetary system. The topic is simply too esoteric, requires knowledge of far too much unusual and slippery terminology, and explaining the accounting does not translate well into words or even pictures (it requires an animated explanation, one day, one day). I will go through each category one by one so everyone can hopefully understand what it means. If you’d like you can also refer to the Bank’s description of the balance sheet. Or just trust my conclusions and skip to the bottom. Here we go…

Advances:

As previously mentioned, advances are loans to banks or the government, in this case specifically the banks that have accounts at the BoC. But before you get your hackles up about our banks needing loans, these are not bailout loans to prop up an insolvent institution, these are temporary bridge loans to cover unexpected shortfalls in the large-value transfer system (the LVTS, which is where banks and the government settle up all their transactions at the end of the day). As you can see, those loans are already being wound down, they will likely be the first item to disappear from the post-COVID balance sheet.

The reason these loans were necessary was likely due to unexpected friction between banks settling with each other in the LVTS; one or more institutions fell a little short and the BoC, as lender of last resort, covered them. The BoC charges them the Bank Rate, and we make a little money off the deal. More on the operating band of interest rates later.

The BoC states clearly it will not disclose the names of the banks, and this is for good reason. The average person simply does not understand how central banking works, and if they saw their bank’s name as receiving a loan it would likely undermine public confidence in that bank and possibly cause a run on the bank. So the books clearly show the loan, we’ll just never know to whom it was made unless we dissected the balance sheets of all the banks in the LVTS and pieced together who had loans from the BoC at that time.

Securities Purchased Under Resale:

Securities purchased under resale agreements is when the central bank buys assets from the private banks, usually government bonds, with an agreement to sell them back at a later date, anywhere from one day to three months. This is normally done in order to influence interest rates and/or neutralize government flows.

This is by far the largest change on the asset side of the BoC balance sheet, and it’s the easiest to spot example of quantitative easing (QE), which the BoC is doing for the first time. In a nutshell, QE is when the central bank injects liquidity (new money) into the system by buying existing financial assets from the banks and other entities. The reason for this is because those assets become less desirable for banks and companies to hold, partly because those assets lose value in the wake of the crisis, but also because those assets are not as “liquid” as money, they can’t be spent like money and must be sold first. By making these purchases the central bank is encouraging an easy flow of credit from the banks because they will be less reluctant to lend if they are flush with billions in liquid cash.

(for the wonks only: one can quibble about the semantics of labeling resale agreements as QE as Governor Poloz has, but in Canada’s case it fits, firstly because we actually rarely use resale agreements for monetary policy, opting for transfers of government deposits instead, and when the activity is so unusually large and intended to be ongoing for the crisis, it is no longer a typical resale)

Canada Mortgage Bonds:

Anyone who’s seen the movie “The Big Short” or delved a little into the cause of the 08/09 Great Financial Crisis (GFC) will be familiar with mortgage-backed securities (MBS). These are when a bank bundles a bunch of mortgages into one big security, and then sells that security to investors, and the investors reap the interest payments of the mortgages. Well there’s a reason Canada did not suffer as badly as other nations during the GFC, and it’s mainly because of how we handle MBS.

First off, our banks are not allowed to invest in any MBS other than Canada Mortgage Bonds, which is why they were not exposed to that market when it crashed in the US. Secondly, our MBS can only be made out of Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC)-insured mortgages, so these mortgages are already safely insured and guaranteed by the government. Lastly, our banks only bundle the mortgages, then the CMHC buys them up, then the CMHC itself sells them to investors. So we have structured this market much more securely and with a lot more oversight and accountability than the free-for-all frenzy that happened in the US.

HOWEVER, the government, BoC, and CMHC seem to be making an exception now, and will “allow lenders to add previously uninsured mortgages into the pool of securities eligible to be bought by the government.” So they are opening the door to precisely the kind of dynamic that toppled the US, let’s hope those uninsured mortgages are from solid borrowers, not simply wealthy foreign investors willing to dump their real estate if the market sours.

In this case, the BoC is not purchasing direct from the CMHC as it does for balance sheet purposes, but rather on the secondary market to support financial market functions, another form of QE as direct support for the banks. Prior to the crisis the BoC always held a few of these, now they’ve ramped it up over 1100%.

Banker’s Acceptances:

A banker’s acceptance (BA) is kinda like a post-dated cheque but guaranteed by the bank, not the company writing the cheque, and is used by small and medium-sized corporate borrowers. This is another form of QE by the BoC, as they don’t normally hold BAs, and the BoC is not buying them direct from the companies, but rather from the banks that guaranteed the BA. Once again, it’s not clear which banks the BoC is buying these securities from, nor which companies they are from.

Commercial Paper:

Here’s where things get interesting. Commercial paper is debt issued by companies but also public entities, like provinces and municipalities. But this is not direct support for public entities, at least not on the surface, because the BoC is buying this debt from banks, not from the public entities themselves, and so it is more QE. But the BoC can buy municipal debt if it so chooses, and was able to do so before COVID, they just won’t lift a finger to fund cities unless doing so supports monetary policy (which I would argue in cities like Toronto it does, because the cost of living, and hence inflation, is higher there and would be even higher if we raised taxes to fund our flagging infrastructure).

Government of Canada Bonds:

Finally we have come to the heart of the matter: direct support for the feds by the BoC. But, of course, it’s never quite as clear as one would hope.

Government of Canada bonds are the main way in which the government issues debt. Private banks acquire bonds either by swapping their excess reserves for bonds in the primary market or by crediting government deposits at the banks with the purchase, and then sell some of the bonds to the public in the secondary market. The tricky part however is how much the BoC bought direct from the government in the primary market and how much it bought on the secondary market to support the financial system. When the BoC buys newly-issued federal bonds direct from the government it is called “monetary financing”. This is sort of the other side of the coin of QE, except instead of creating money to buy existing assets, it creates money to buy new assets, injecting the government with new money.

This mechanism of monetary financing is the subject of much debate in Canada (I’ve written a VERY in-depth paper on the subject), as it is proof of how our government can easily use our central bank to create whatever funds it needs without ever paying a dime of interest to the banks. It is monetary financing that kick-started the BoC in 1935 to begin ending the Great Depression, made possible our funding of WWII, and aided the government throughout the post-war economic expansion.

After neoliberalism set in starting in the 70s we curtailed this power more and more, but unlike most central banks that are forbidden from the practice, we actually use monetary financing EVERY time the feds issue new bonds and the BoC snaps up a percentage at auction. Without painstakingly disaggregating the data by poring over the various purchase results we cannot tell precisely how much monetary financing we increased since COVID hit, but it’s somewhere in the $50 billion range.

Provincial Money Market:

This is perhaps the MOST intriguing and encouraging change in the BoC balance sheet. The provincial money market is where provinces issue bonds, it’s their primary market. What makes this so intriguing is that seemingly for the first time ever the BoC is doing monetary financing for provinces. Yes, you heard that right, the BoC is creating new money to buy debt directly from the provinces AND it’s possible the BoC has created new deposit accounts for them too (more on this later).

Alot of the debate about the BoC and Canada’s past funding of public works centered on the notion of the BoC making loans to the feds, provinces, and cities. Unfortunately I’ve had to dispel a lot of myths about this, as it is a misinterpretation of the function of a central bank and the loans the BoC has in fact made. As per the loan provisions of the BoC Act, they are NOT meant as loans to fund projects; just like advances they are temporary bridge financing to cover a shortfall in expected revenues, which is why the loan provision terms are so limited in amount and time frame. But monetary financing is a horse of a different colour, it’s like a back door “loan”, a way to provide funding that uses newly created money and does not require paying interest to the private sector. Another phrase for it is “public money creation”: money created by a public institution for public use.

This is one change the BoC should consider keeping, especially as it can help ease the debt burden some of our provinces suffer under. But federal and provincial jurisdictions are closely guarded, we’ve seen how provinces become the fiefdoms of ideological demagogues (especially Conservative ones) and how the feds will or won’t cooperate with various Premiers (and vice versa). Supporting the provinces in this way would likely be seen as letting them off their fiscal responsibility hook, and so the feds would be loathe to do it for the same reasons they don’t really do it themselves: they cannot appear to favour the public sector and must remain fiscally neutral in the eyes of the neoliberal financial world. This means you do not run deficits without matching the deficit spending with bond issues to the banks, else the neoliberal world will punish you with divestment, lowered credit ratings, lowered exchange rate, and worse comes to worse if you really push the envelope, crippling sanctions.

Treasury Bills:

Treasury bills (T-bills) are simply another form of federal debt like bonds; they just pay out interest differently. The changes in this category are pretty much the same analysis as government bonds: some were likely bought direct from the government (monetary financing), some were likely bought on the secondary market to support the financial system (QE).

All Other Assets:

This category is insignificant, it includes property and equipment, intangible assets and other non-investment items, and did not change in any meaningful way.

On to the liabilities…

Notes in Circulation:

This is cold hard physical cash (notes). As a brief aside, the word “cash” is a prime example of the intentional ambiguity of bankspeak. In central bank terms, “cash” can mean the same thing as “reserves” or “settlement money” or “high-powered money”, it’s basically referring to fully liquid deposits, and usually does not refer to physical notes. Another way to put it is “cash” is any deposit easily converted into actual physical cash. Not knowing this can make reading about central bank actions very confusing.

Normally this is the largest liability on the BoC’s balance sheet and requires the most acquiring of assets to match it. It is demand-driven by the public, meaning the BoC only provides as many notes as the banks are asking for according to the needs of the public. It says “circulation” because the notes are just paper until the BoC officially circulates it by swapping it for reserves with the banks. The government can have billions of notes printed waiting in a warehouse, it does not count as “money” until the BoC circulates it.

The good part is that the demand for notes has barely changed, meaning there are no bank runs or people withdrawing large amounts of notes. Another interesting thing to note about notes (pun intended) is that they are the ONLY access to central bank money the public has. Despite the fact deposit money in a private bank is our primary medium of exchange, it’s not actually legal money like notes, it’s just the PROMISE to pay legal money on demand. Deposit money in private banks is not defined in the Currency Act, it is de facto money, and we have allowed private banks the power to create it at will.

All Other Liabilities and Capital:

Just like “All Other Assets” this is not a significant item on the balance sheet. The “capital” part is likely just the leftover equity after all else has been accounted for. However I would like to know what exactly changed that it decreased in amount.

Government of Canada Deposits:

As yet another example of confusing bankspeak, Government of Canada deposits are also known as the Consolidated Revenue Fund aka the Receiver General Account (RG account). This is where all spending comes from and all taxes go into. That’s why you make your tax payment to the Receiver General, and why all government cheques come from the Receiver General. It’s the government’s account at our central bank.

The change in this account is more or less (in the aggregate) the result of new monetary financing, the BoC bought debt direct from the government and credited this account with newly-created money. And the BoC does this on a regular basis, it just used to do it more (the main subject of my previously mentioned paper).

One might be confused considering the government’s various announcements about financial support of the economy not really jiving with this increased amount. Well, that’s because the government NEVER has on hand all the cash they need for their spending in a year, it’s a daily simultaneous flow of spending going out and taxation going in. The BoC anticipates these government flows and will take pre-emptive action to ensure the RG account has what’s needed for any particular day of government spending, either building up reserves for a big spend, or auctioning them off when they’re not needed.

This also means the federal government does NOT depend on your tax dollars in order to spend on public services (whereas without a central bank provinces and municipalities do depend on tax dollars to fund themselves). The federal government does not need to save up tax dollars first before it can spend on the public, it spends first and taxes later, or more accurately, spending and taxation both occur at the same time every day in varying amounts relative to each other. Point being though, federal government spending is NEVER constrained by tax dollars, if it were very little would happen until after tax time rolled in and the government saw how much they had to spend.

Other Deposits:

Remember when explaining provincial money markets I said I’d get back to new deposit accounts? This is another case where because of the BoC’s stated policy of “confidentiality considerations” we may never know who exactly owns these deposits, but it seems very possible a large chunk of them is whichever provinces the BoC bought bonds directly from.

“Other deposits” is a newer entry on the BoC balance sheet, I can’t say for sure without really digging deep, but it’s entirely possible this is the first time the BoC has ever granted deposits to entities other than the federal government and banks. According to the BoC website “These include foreign central banks and international financial institutions, designated clearing and settlement systems, and other domestic federal government agencies.” As this COVID intervention is likely for domestic entities, the BoC likely gave new deposit accounts to smaller banks not part of the LVTS, or possibly even to some of the larger corporations it’s supporting with QE, and lastly, maybe even some of the provinces or larger cities. We may never know.

Members of Payments Canada:

And finally we come to the aggregate result of QE, the increase of deposits of the private banks that are members of Payments Canada. The members are the largest banks/financial institutions in the country, they all participate in the LVTS, and they are for whom most of this hubbub is about. Increasing these deposits (aka “injecting liquidity”) by buying up financial assets from these banks is what is meant to grease the wheels of money markets and bank lending, to ensure continued easy access to credit.

You will note the amount of these deposits is barely visible before COVID. That’s because the BoC has a 0% reserve requirement, since 1994 our banks have not been required to hold any reserve money as a percentage of their deposits, they can lend or spend their excess reserves as they see fit. But keeping reserves at the BoC earns the bare minimum in interest (the Deposit Rate), they’d rather swap them for a variety of government bonds earning various rates of interest for various time periods which they can then sell to investors. So they keep a very specific minimum at the BoC, which did not fluctuate week after week before the crisis.

(wonks only: in a bizarre twist, the BoC is violating its own interest rate operating band. The target for the overnight rate aka the policy interest rate aka the key interest rate (more confusing bankspeak giving everything multiple names!) is a 0.5% band, the policy rate is at the center, the Bank Rate (the rate banks pay on advances from the BoC) is 0.25% higher and the Deposit Rate (the rate the BoC pays on deposits) is 0.25% lower.

So when the policy rate is 0.25% as it currently is, the Deposit Rate should be 0%, we should not be paying banks interest on their deposits. But for whatever reason the BoC is not going to the actual effective lower bound, it’s staying just above it, so all the new deposits we created for the banks are still earning 0.25% when they should be earning squat. Even with all that extraordinary support we’re still ensuring the banks get their pound of flesh).

If you think all this cajoling and bending over backwards to ensure the banks do their job and fulfill their function as providers of credit is a bit of a farce, you’re not alone. The entire monetary system is set up not to control banks and their de facto money creation, but rather to gently influence them, leaving as much to the “free” market as possible.

The BoC does not control the supply of money, at all, it attempts to influence the cost of credit, primarily through its actions in markets to support its intended interest rate. It’s yet another monetary dance, part of the illusion of finance, and it’s the reason I advocate for nationalizing the banking system. Having a fully public banking system would eliminate the necessity and expense of overnight money markets, neutralizing government flows, selling bonds, and doing the specious dance of leveling the central bank’s balance sheet. Money creation should be a public utility, not one of the most profitable private businesses vacuuming billions of dollars from the public every quarter.

WHAT DOES IT ALL MEAN?

Those COVID “funds” are nothing more than numbers in a computer conjured out of thin air, the feds have the power to create as much as they want at any time. Yes, money is imaginary, to say we don’t have enough is to admit we don’t have enough imagination.

It all boils down to this: when Justin Trudeau tells a disabled veteran “They are asking for more than we are able to give right now” he is either telling a bald-faced neoliberal lie to deny funding the needs of Canadians, or he is supremely ignorant of how our monetary system works and is completely oblivious to the fact he’s telling a neoliberal falsehood. That also goes for every politician claiming we need to “find the money” or who foments hysteria around debt or deficits. These are the falsehoods standing in the way of truly improving life for ALL Canadians. Whether lying or ignorant, can such people really be trusted with our collective future?

Adam Smith, 21st Century