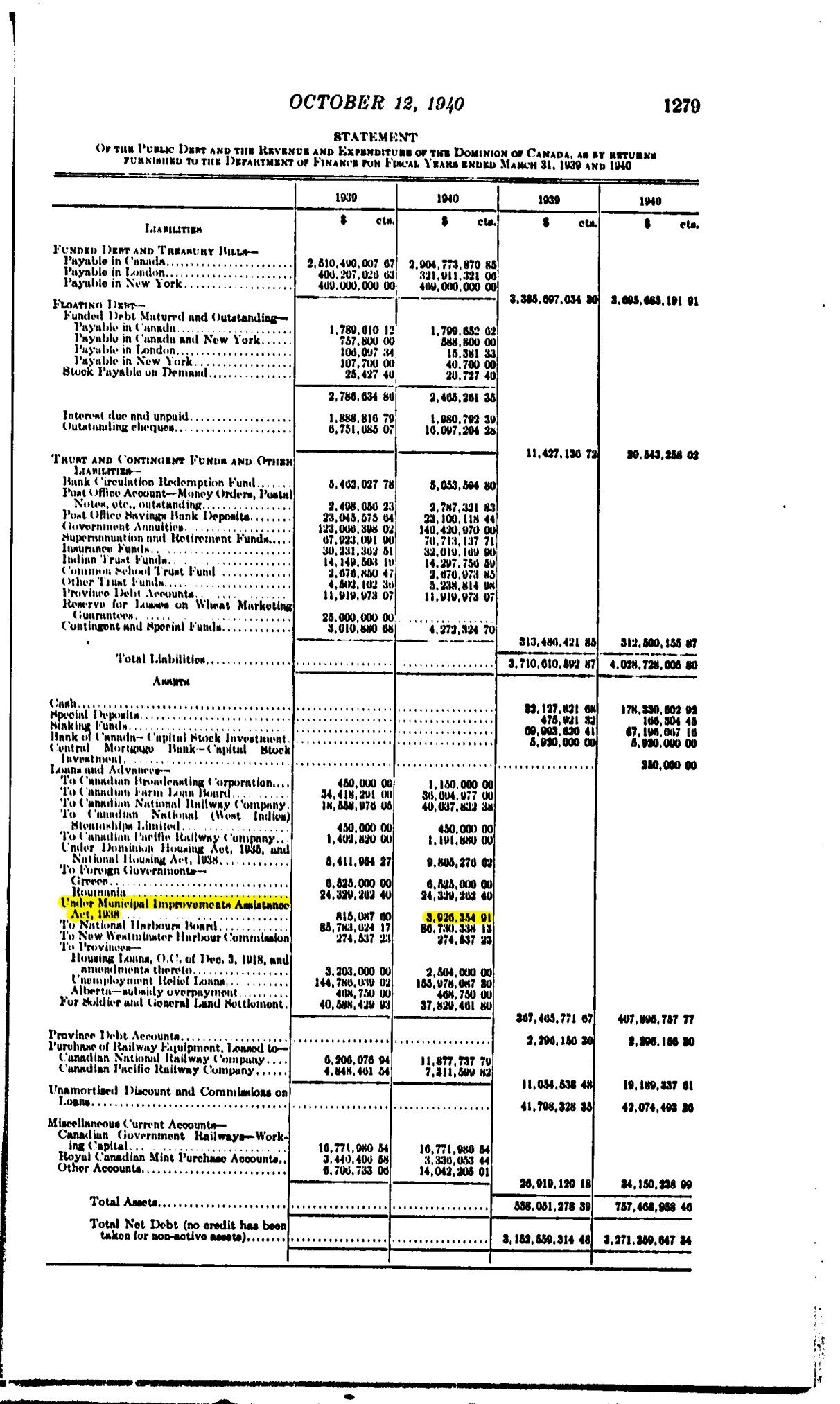

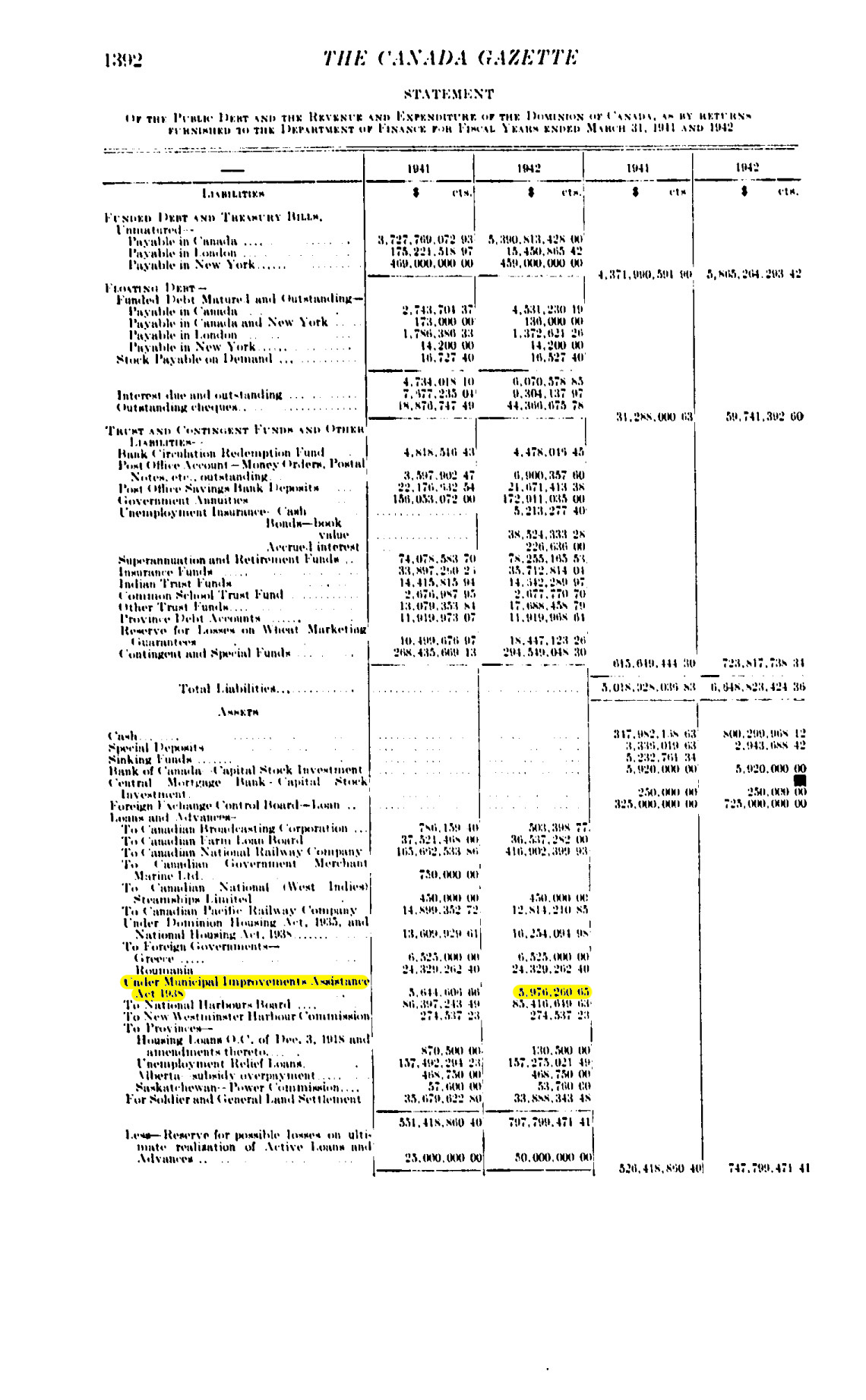

It has been claimed by many that the federal government never made loans directly to cities for infrastructure. This is incorrect, one just needs to dig deep enough into the Canada Gazette archives. There one will find the Municipal Improvements Assistance Act 1938, and the corresponding loan value on the government’s balance sheet. The peak was in 1943 when the total value reached $3,740,716.44. That is $53,644,340.16 in 2017 dollars, at a time when our population was only 11,795,000, making it around $4.50 for every person alive at the time.

After 1943 the government seems to have ended the program, but still has a line about loans and advances to provincial and municipal government, which continues for years afterwards. Once upon a time federal support of local needs was much higher. The full text of the Municipal Improvements Assistance Act is here:

Here’s a quote from 1939 about the good the Act was doing:

“34. Under the Municipal Improvements Assistance Act, 1938, the Government approved loans prior to March 31, 1939, amounting to $3,143,000 to municipalities to enable them to finance the construction of municipal self-liquidating projects. As at March 31, 1939, the amount actually paid out on such loans was $815,000. These loans bear interest at the rate of 2% per annum and are amortized over a period not longer than the estimated useful life of the project. The province in which the municipality is located is required to guarantee the payments of interest on and amortization of any such loan.”

Invaluable!

Invaluable.

I concur… I was very upset when the Mulroney government issued an Order In Council eliminating C143, effectively forcing Municipalities to the market

to finance their infrastructure improvements. No wonder property taxes went seriously north after this slight of hand. This amounted to a subsidy to the banking system on the backs of taxpayers.

Is Monetary Financing Inflationary? A Case Study of the Canadian Economy, 1935–75

by Josh Ryan-Collins*

Associate Director

Economy and Finance Program

The New Economics Foundation

October 2015

http://www.levyinstitute.org/pubs/wp_848.pdf

Extracts:

> As shown in figure 1, between 20–25% of Canadian public debt was financed

> and held by the central bank and government from the end of World War II up to the early

> 1980s but inflation was below 5% right up until the early 1970s…….

> Here we focus on the monetary financing activities of the Bank of Canada to support: 1) the

> lifting of Canada out of the Great Depression of the 1930s and the subsequent war

> mobilization, which involved substantial direct and indirect (via the chartered banks) credit

> creation to fund government war spending; 2) postwar recovery and industrialization in the

> 1950s and 1960s, which saw the central bank support government spending through the

> maintenance of fixed low rates of bond and Treasury bill financing; and 3) the Canadian

> small business sector, through the Industrial Development Bank (IDB), a wholly owned

> subsidiary of the Bank created in 1945, which lent directly to small and medium-sized

> businesses across Canada up until 1975 where it was transferred to government ownership.

> The Bank conducted four main kinds of activity in this area (Neufeld 1958a, 81–111). First, it

> undertook direct deficit financing through purchases of government securities from the

> government; secondly, it pumped large quantities of cash reserves into the chartered banks via

> bond purchases and maintained a low bank rate to ensure they had sufficient liquidity to

> further finance the government via direct purchase of securities. This can be seen as a form of

> indirect monetary financing via private bank monetization of government debt (Watts 1972,

> 54). Thirdly, via these two operations and the development of a short-term Treasury bills market, the Bank ensured low yields on government bonds throughout the period, thus reducing the cost of deficit-financing; fourth, working with the Department of Finance, it developed illiquid “deposit certificates”—usually with a six-month maturity—that enabled

> the government to raise short-term finance directly from the chartered banks (Ascah 1999,

> 108–11).

> In the prewar period between 1935 and 1939, the Bank played a major role in Canada’s

> recovery from the Great Depression, funding overtwo-thirds of government expenditure over

> these five years.

> During the war period, $517.8 million of securities were bought directly from the government

> with newly created central bank money and by converting numerous maturing securities into

> new Government of Canada issues (Neufeld 1958a, 145; Mcivor 1958, 174). As Plumptre

> (1941, 155–56) remarks, the effect of this increase in note issue was to provide “a sort of

> interest-free loan to the Government through the medium of the Bank of Canada.” The Bank

> issued the notes at virtually zero cost to itself, whilst the profits paid to it by the government

> for holding government debt were all paid back to government which owned all of its stock.

> From 1941 to 1943, the government borrowed $1,165 million directly from the chartered

> banks, of which $715 million were illiquid deposit certificates issued at three-eighths of 1%

> (Neufeld 1958a, 133).

> The central bank accommodated such purchases and maintained a

> low yield on government debt (2.2%) by providing the chartered banks with sufficient

> liquidity to enable them to maintain their preferred cash ratio of 10% (Neufeld 1958a, 134).

> This policy continued in 1944 when the government reduced the bank rate and provided the

> banks with “more reserves than they had ever had before” (Neufeld 1958a, 138). As a result,

> the chartered banks bought huge quantities of government securities and ensured easy money

> conditions for the government and general public.

Industrial Development Bank (IDB)

> In contrast to most public development banks,

> which were capitalized with taxpayer funds

> and leverage-in private finance, the IDB was entirely funded via money creation by the Bank

> of Canada during its 31-year existence. The IDB was initially funded by the purchase of $25

> million in equity stock by the Bank of Canada. By end of 1947, all $25 million of stock had

> been taken down leaving the IDB with significant surplus funds which were invested in

> government securities. By 1951, virtually all equity funds had been used up in the IDB’s

> loans. It made a number of further sales of bonds to the Bank of Canada to maintain its capital

> at the same rate as Canadian government three-year bonds.

> As well as supporting SME financing, the Bank of Canada continued its policy of ensuring

> easy and cheap finance for government to support fiscal expansion and maintain the policy of

> full employment. Monetary policy during this period diverges significantly from the NMC

> and CBI approaches outlined in section 2.3. Rather, it was closer to the “Functional Finance”

> (Lerner 1943) and “Modern Monetary Theory” schools (Wray 2012) outlined in section 2.4.

> Changes to the short-term interest rate were generally not seen as a useful policy instrument

> (Neufeld 1958b) and fiscal policy took on much of the responsibility for dampening the

> inflationary surges that inevitably followed the war, via increases in taxation and repeated

> budget surpluses (Deutsch 1957). Although the bank did make use of open market operations,

> it also employed more direct methods. These included variable secondary reserve

> requirements, purchase and resale agreements, management of government deposit balances,

> interest rate agreements between the Bank of

> Canada and chartered banks, and quantitative

> credit guidance and moral suasion, both formal

> and informal (Neufeld 1958a, 75–80; Mcivor

> 1958, 156–57; Chant and Acheson 1972). Moral suasion was defined by the Bank as: “a wide

> range of possible initiatives by the central bank designed to enlist the co-operation of

> commercial banks or of other financial organizations in pursuit of some objective of financial

> policy” (Bank of Canada 1962, 37).

> The low interest rates engineered by the Bank’s control of the bond market supported a huge

> expansion in production in the period 1945–70, with a good part financed by government

> capital spending which reached around 20% of total fixed capital investment for most of the

> 1960s (figure 6). Federal government capital expenditure funded highways, airports, bridges,

> schools, hospitals, and other physical infrastructure. The rates of growth of both GDP and

> productivity followed the pattern of public capital formation during this period (Seccareccia

> 1995) but then began to decline in the late 1960s and 1970s.

> During the period 1960‒75, the federal government also introduced virtually all of the major

> policy innovations that make up Canada’s system of social programs: Canada-wide Medicare,

> universal pensions, the modern unemployment insurance system, and cost-sharing with the

> provinces for higher education and welfare. Despite this massive expansion in spending,

> budgets remained roughly balanced. The average federal deficit from 1950 to 1980 was an

> insignificant 0.3% of GDP (Stanford 1995, 116). Inflation also remained low and stable,

> ranging between 2 and 5% (figure 1).

> Accompanying the monetary targeting, the proportion of government debt held by the Bank was reduced from 20% to 7% in the space of just threeyears (figure 8). With double-digit interest rates on long- and short-term government debt

> (figure 3), this inevitably led to a jump in the proportion of government spending that had to

> be committed to interest payments that leaked

> out of the public purse. Rather than such

> interest payments returning to the government as

> central bank profits, they were now flowing

> to the private sector.

> The 1935‒70 period saw the Canadian economy recover quickly from the Great Depression, weather the

> Second World War, make a rapid transition from war to peace, and then enjoy a 25-year

> period of relatively stable and high growth with rapid industrialization. The period also saw

> declining public debt, consistent budget surpluses, and full employment. The Bank of Canada

> played a key supporting role by directly and indirectly financing government debt, controlling

> government debt markets and domestic credit creation via quantitative controls and “moral

> suasion.” For the majority of the period, the Bank was not independent of the government and

> its primary objective was full employment and growth rather than price stabilization.

______________________________________

Modern Monetary Theory in Canada

http://mmtincanada.jimdo.com/

Excellent info, that link was in our paper on the BoC vs CIB.